#BWStory

Bauhaus in SouthWest Germany

On the 100th anniversary of the Bauhaus art and design school, we find out what became of the Big Idea and how it evolved in Stuttgart’s Weissenhof Estate, in Karlsruhe’s Dammerstock and at Ulm’s School Of Design.

“Colourful is my favourite colour.”

Walter Gropius, Bauhaus Founder

–

As soon as you step over the threshold, you feel at home. With its brightly coloured walls, the narrow staircase is welcoming. The living room has a window that looks out on greenery. And, this room can be transformed quickly into two bedrooms. The beds appear from the cupboards; a sliding wall separates the parents’ beds from the children’s beds. Yet, although the design is clean and contemporary, the atmosphere is cosy. Welcome to the semi-detached houses designed by the Swiss-French architect, Le Corbusier! Built back in 1927, these are part of the Weissenhof Estate in Stuttgart.

A visit is like a pilgrimage for anyone interested in design. One house is now the Weissenhof Museum; the other is still a home. Like a time machine, it provides a glimpse back to the days when Bauhaus ideas were shockingly new. In 2016, the Le Corbusier houses were designated as a UNESCO World Heritage site. Throughout 2019, the museum is celebrating the centenary of the founding of the Bauhaus.

Back in 1927, some 500,000 people came to see the pioneering new-look houses.

The flat-roof dwellings were built for a special exhibition showcasing what was later dubbed the “International Style” of modern architecture. As Anja Krämer, the head of the Weissenhof Museum, says, opinions on them have long been divided. One Berlin newspaper declared: “We Berliners are envious of Stuttgart.” But, when Mies van der Rohe, the development’s artistic director, showed local architects the plans, they said the estate looked like an “Italian mountain nest”. There was talk of "amateurism”. Van der Rohe was offered a counter-proposal, which he rejected.

Decide for yourself. Of the 33 originally built, several were destroyed during World War Two. But 22 are still standing; a number are still homes.

The Haus auf der Alb

Only two Stuttgarters worked on the Weissenhof Estate project. One was Adolf Gustav Schneck. In 1929–30, he built the dazzling white Haus auf der Alb, an imposing rehabilitation centre in Bad Urach. Today, this is now used as a political study centre. As well as hosting seminars, participants can stay the night in the Modernist rooms.

Stuttgart was a source of inspiration for the Bauhaus

After World War One, Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius wondered how life could be improved for the people of Germany and how people would live in the future. This sort of philosophising is what made the Bauhaus so much more than an art or even an architecture school. He encouraged his students to think about the “Big Picture” and about social behaviour. And he encouraged them to break down the borders between architecture, design and art. That legacy can still be seen in design classics that are in our living rooms today.

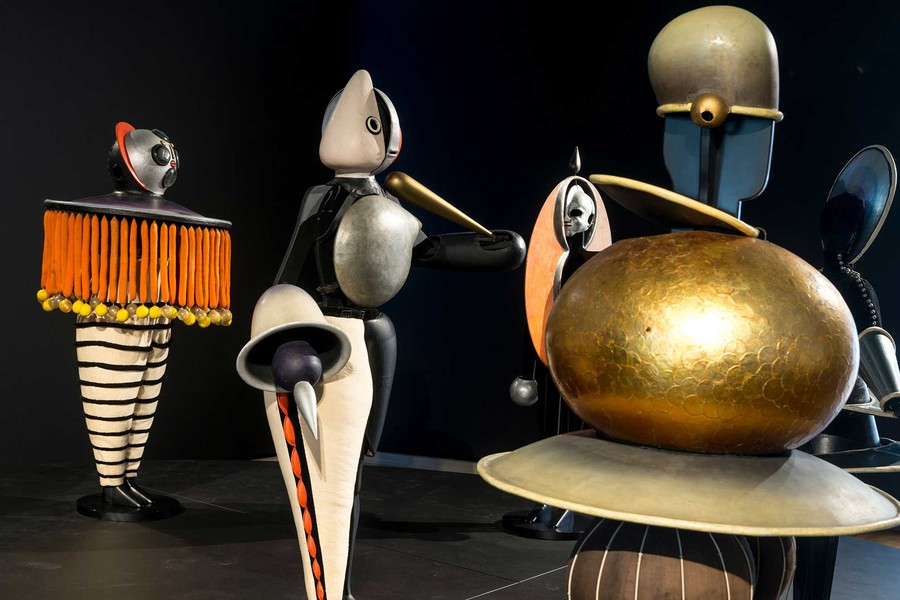

The Triadic Ballet in the Staatsgalerie

Some of the ideas that were being developed in Weimar, in Thuringia, back then were actually imported from Stuttgart’s State Academy of Fine Arts. Two students, who studied under Adolf Hölzel became Masters (professors) at the Bauhaus. One was the Swiss artist Johannes Itten, whose theories on colour have been so influential; the other, Oskar Schlemmer, was a Master of Form. Born in Baden-Württemberg, Schlemmer is renowned for his Triadic Ballet. See the figurines for this important dance work in the main gallery of Stuttgart’s Staatsgalerie. With music composed by Paul Hindemith, this experimental ballet premiered in Stuttgart in 1922 and very much represented the spirit of the Bauhaus. Although Gropius founded the Bauhaus, he was involved in projects away from Weimar. Examples include the Dammerstock Estate in Karlsruhe.

The Dammerstock: Light, airy and green

What use are high ceilings if hardly any light comes through the windows? What child wants to play in a small, cramped backyard? According to tour guide, Gabriele Tomaszewski, the plan at the Dammerstock was to create buildings with “lots of light, lots of air and lots of space”. And the residents were going to be ordinary citizens from Karlsruhe. Because of the Great Depression, the project was never completely finished, but you can still walk through this leafy, airy neighbourhood. There is plenty of room between the rows of buildings; the houses are built so that the sun shines into the bedrooms in the morning and into the living rooms in the afternoon. No wonder they are especially popular with families.

Gaststätte in der Dammerstock Siedlung in Karlsruhe

Open-air showroom for modern architecture

Walter Gropius won the competition to redevelop the city of Karlsruhe in 1928. His job was to bring in other successful participants in the competition and co-ordinate their designs. The result was a kind of open-air showroom for various styles of modern architecture. Unfortunately, the project was never fully realised. First was the economic crisis; later the National Socialists come to power and they rejected the new building project.

The Bauhaus school, which started in Weimar, moved on to Dessau. But, what happened when the National Socialist movement closed it down in 1933? Did the Modernist ideas wither away? Certainly not! Many artists emigrated. Some headed to Chicago and Tel Aviv, where their legacy is still visible today. But the Bauhaus heritage also survived in SouthWest Germany. In Ulm, the Ulm School of Design (HfG) picked up the baton in 1953. When it comes to innovative thinking, the HfG was rated second only to the Bauhaus.

More design classics

The Ulm School of Design (HfG) continued the Bauhaus multidisciplinary philosophy, which integrated technology, craft and art. Students experimented in the areas of graphic design, product design, architecture and film. The school closed in 1968, but the HfG building that was designed by Max Bill, a Swiss architect, still stands today. And the legacy continues, from the Lufthansa “flying crane” logo to stackable ceramic tableware. But the HfG has something much more important in common with the Bauhaus: its political legacy.

“Time and again we saw that important matters of the present were not being dealt with.”

Inge Aicher-Scholl, co-founder of HfG Ulm

–

Museum director Martin Mäntele calls it the "foundations of the anti-Fascist movement", thanks to the efforts of one of the university’s founders, Inge Aicher-Scholl, who was the sister of Hans and Sophie Scholl. At the time, Max Bill said that "All the activities at the university are focused on helping to build a new culture."