Groundbreaking development

The Avant-Garde in Stuttgart

© TMBW, Foto: Gregor Lengler

BW Story - Hirsch & Greif

Stuttgart's Pioneering Role in Modernism

The Roaring Twenties were not confined to Berlin. Stuttgart was just as progressive, embracing greater freedom as well as edgier art and entertainment. The city reflected all facets of the modernist movement.

Modernity, Art, and Freedom

The Roaring Twenties

The 1920s were an exciting time in Stuttgart. The world premiere of Oskar Schlemmer's Triadic Ballet in 1922 broke barriers in the world of dance. At the same time, the city was rapidly becoming the automobile capital of the world. By 1924, Stuttgart citizens owned more cars per capita than Berlin citizens. Mercedes-Benz advertised cars for the so-called "new woman," who was independent and spirited, with bobbed hair and dramatic eye makeup. In 1927, journalists came from as far away as New York and Moscow to report on the daring architecture of the new Weissenhof Estate. And in 1929, Josephine Baker, the legendary scantily-clad entertainer, performed at Stuttgart's Friedrichsbau cabaret club, a venue that remains popular today. Movie theaters, dance halls and swimming pools flourished. Working hours were reduced, giving employees more free time to enjoy themselves. Better public transportation gave them more mobility. Stuttgart buzzed with modernity, art and freedom.

A new style of architecture

Stuttgart, Birthplace of the Bauhaus

Of course, many of Europe's great cities enjoyed this exciting era. What was called the Roaring Twenties in Britain and Les Années Folles in France was far more than just a post-war phenomenon in Berlin. "At the time, Stuttgart had a very modern image," says Anja Krämer, who runs the Weissenhof Museum. And Stefan Egle of the Staatsgalerie art museum agrees: "Stuttgart was a hotspot for museums and art galleries. People flocked to the Staatsgalerie to see Expressionist paintings."

As early as 1905, an impressive number of young artists were studying under Adolf Hölzel at the Stuttgart State Academy of Fine Arts. The so-called "Hölzel Circle" included artists such as Oskar Schlemmer, Johannes Itten, Willi Baumeister, and Ida Kerkovius. "You could say that we invented the Bauhaus," says Nils Büttner, professor of early modern and modern art history at the State Academy of Fine Arts. Students who studied with Hölzel attended workshops where they developed ideas that Schlemmer and Itten took with them to the Bauhaus in Weimar.

Museums, Tower, and Funicular

The Legacy of the 1920s in Stuttgart

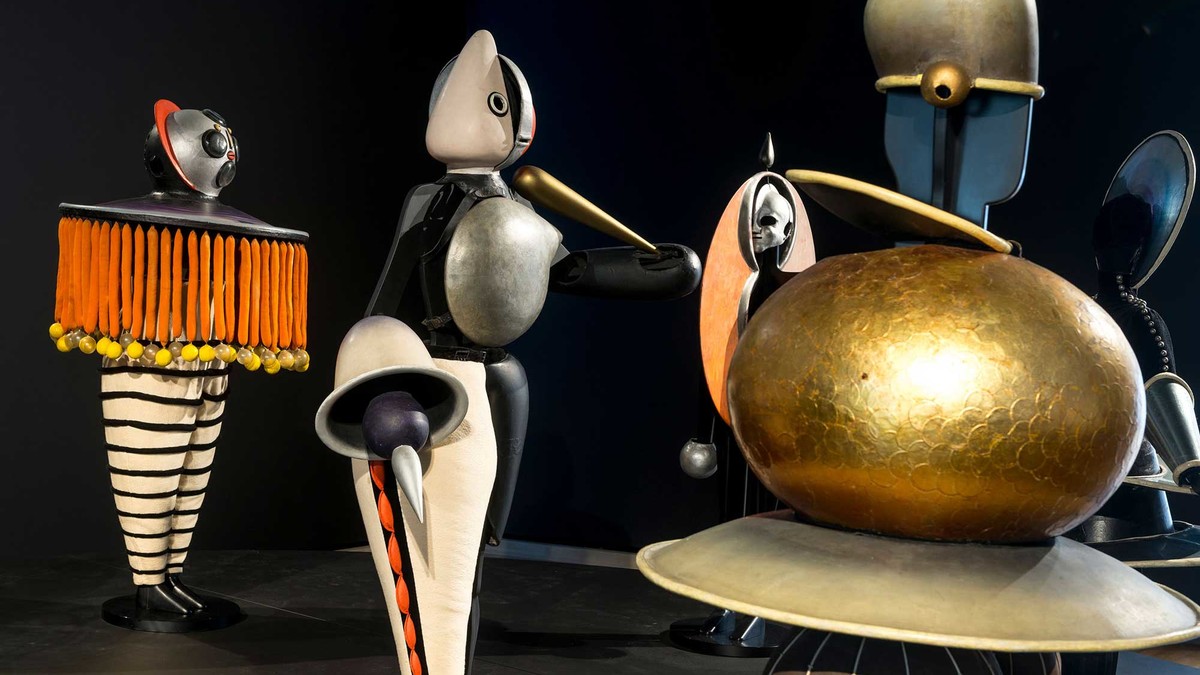

So where in Stuttgart can you see the legacy of that era today? Start with the Staatsgalerie art museum, where you can see Schlemmer's Triadic Ballet figures and other important works by the artist. There are also paintings by Willi Baumeister and Ida Kerkovius, along with other important international works from the modernist era. Stuttgart's art museum on the Schlossplatz square also helped to establish the city's reputation for exciting art in the 1920s. Among the many paintings by Otto Dix is "Metropolis," a triptych of three harrowing nocturnal city scenes.

"The Triadic Ballet is the key artistic work of that era."

– Steffen Egle, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart

But it's not just artwork that remains. The Tagblatt Tower, built in 1924 as Germany's first reinforced concrete high-rise building, has become a landmark. Once home to the world's tallest paternoster-style elevator (15 floors), it now houses the Unterm Turm cultural center with theaters and cultural facilities.

The wooden funicular railway opened in 1929. It ran - and still runs - from Südheimer Platz Square in the western suburb of Heslach up to the Waldfriedhof cemetery. Important graves there include those of Oskar Schlemmer and Adolf Hölzel.

Order a Beer!

A Bar from 100 Years Ago

The grandiosely named Palast der Republik (Palace of the Republic) is actually a bar-kiosk. Now a hip spot where Stuttgart's younger generation meets for a beer, this 1920s building was originally a public toilet. Then there are the Waldheime, rustic cottages built for workers to enjoy the countryside. In Heslach, west of the city, many are now beer gardens where you can order a beer with a plate of Maultaschen (famous Swabian ravioli).

The spirit of the twenties lives on in the Jigger & Spoon bar, a cocktail bar in a former bank vault. To enter, ring the bell and take an old elevator down two floors. "We wanted to recreate a Prohibition-era American speakeasy," says Eric Bergmann, one of the owners. It took 10 months to transform the vault, with its 3-foot/90-centimeter-thick walls, into what looks like a 100-year-old bar. But along with the massive doors and iron bars, there is Wi-Fi, a wine list and a modern cocktail menu. The past meets the present underground; the result is a party!